Wednesday the Federal Open Market Committee did the expected, by announcing a “tapering” off of its $85 billion monthly purchases of long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBS’s), citing “the cumulative progress toward maximum employment.” Thursday the BLS announced that weekly jobless claims rose to their highest level in nine months. Ouch.

Granted, the spike in jobless claims might not mean much, as they can be volatile, especially around holiday time, and indeed the four-week average of jobless claims “only” rose to its highest level in one month. Even so, the “progress toward maximum employment” has been glacial, if it can be called progress at all. The media have trumpeted the good news in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) latest employment report, which found that the standard unemployment rate fell from 7.3% to 7.0%, its lowest level in five years, and employers added 203,000 jobs. That’s fine, but it’s also just one month. Let’s look at the past year, from Nov 2012 to Nov 2013, using the Households Survey numbers in the employment report.

In the past year the adult US population grew by almost 2.4 million. The number of people “Not in labor force” (neither employed nor actively looking for a job) also grew by slightly more than 2.4 million. The total US labor force actually fell by 25,000, and the employment-to-population ratio also fell slightly, from 58.7% to 58.6%. While it’s good news that total employment rose by 1.1 million and unemployment (and people who say they currently want a job) fell by 1.1. million, the biggest growth sector by far is “Not in labor force,” again with 2.4 million. The employment/population ratio is exactly the same now as it was four years ago, in Nov 2009. This is not progress.

I wouldn’t be an economist if I never said “On the other hand,” however, and on that hand we have the “Establishments Survey” that furnishes the other half of the BLS report. The unemployment and employment/population rates come from the Households Survey; the payroll numbers (e.g., 203,000 jobs added) come from the Establishments Survey. Average monthly payroll growth for the past year was 191,000 jobs, or more than double the puny job growth in the Households Survey (1.1 million / 12 months = 92,000 jobs per month).

What would victory look like on the jobs front? I would say 5% unemployment, which the economy had for 35 straight months in the mid-2000s, or less. (And I would want the reduction to come from job growth and not from people leaving the labor force.) How far are we from 5% unemployment? The Atlanta Fed’s handy jobs calculator has the answer. If the economy keeps on adding 191,000 jobs per month, we return to 5% unemployment in three years. If it adds just 92,000 jobs per month, we never get back to 5% unemployment, unless the labor force does a whole lot of shrinking. If we split the difference and figure the correct figure is right in the middle at 141,500, then we get there in seven and a half years, in early 2021.

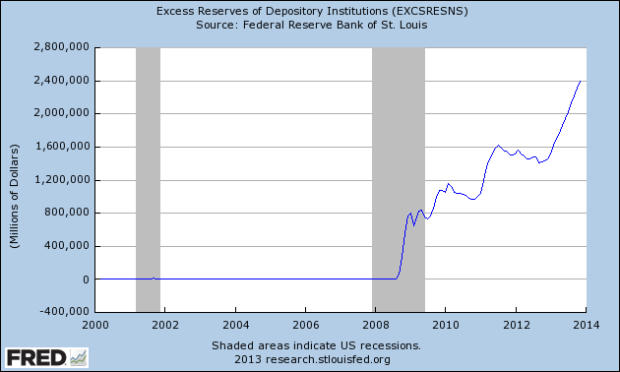

Back to the taper. The labor data suggest a need for more, not less, monetary stimulus, but how much stimulus were those emergency bond-buying programs providing? All we know is that they created $85 billion in new bank reserves each month. For the programs to work, banks needed to loan out those reserves. Not much of that has been happening:

Real estate and consumer loans are flat. Business loans are rising but not fast enough to return to their trend level. (Which, by the way, is true of just about every other macro aggregate — household consumption, business investment, etc.) Just as the fastest-growing occupational category is Not In Labor Force (NILF?), the most dramatic growth on bank balance sheets is excess reserves:

This is what pushing on a string looks like. Maybe the taper is causing the volume of loans, however meager, to be larger than it otherwise would be, but it’s hard to believe it’s making a world of difference. An oft-cited study published by the Brookings Institution found that the MBS purchases had managed to lower mortgage rates but that the Treasury bond purchases had not lowered long-term Treasury rates. And lowering long-term interest rates, as the bond buying is supposed to do, is only part of the game. Banks have to make loans at those rates. As we saw in the first graph, not nearly enough of that is happening. And the economy probably has to improve a lot more before banks are eager to lend and people are eager to borrow. Catch-22, yes.

All in all, the slight taper, from $85 billion to $75 billion a month, is unlikely to do noticeable harm, since the bond-buying program doesn’t seem to be making a big difference in the first place. Declaring victory, or even declaring substantial progress, on the employment front is foolish, but tapering is another story. Alternative policies, like ending the payment of interest (currently 0.25%) on bank reserves, might be preferable to the long-term bond-buying, but it’s clear from the last few years that Fed cannot be the main driver on the road to recovery. Congress could, through fiscal policy, but won’t, preferring austerity to stimulus, when it isn’t shutting down the government entirely. It looks like we’ll have to cross our fingers and hope for the “natural forces of recovery” to work their magic.